Spencer Gore was ‘a perfect modern’ who found inspiration in the humdrum urban landscape. His paintings of Camden Town streets were exemplary of modernist painting in London before the Great War.

InSight No. 132

Spencer Gore, From a Window in the Hampstead Road, 1911

Regarding art from the time of Manet onwards, there is controversy among art historians about the degree to which considerations of form and content respectively shaped the development of modern art. Was it the urge to produce delicious painterly paintings that encouraged the adoption of subjects with flattened features and rectilinear structures, or was it the discovery of modern subjects – city streets, bed-sitting rooms, public advertising – that necessitated a framework of visible brushwork and heightened colour? The same question applies to the work of Spencer Gore (1878—1914) who knew how to make ‘a panel of encrusted enamel’, yet whose oeuvre ranges from urgent contemporary scenes of music halls and city streets to landscapes of bucolic countryside.

In Gore’s painting From a Window in the Hampstead Road, the street scene is ordered by the mullions and transoms of a window frame and the upright lamp post outside. These unambiguously representational features would be comprehensible to Alberti, who in the fifteenth century regarded his canvas as ‘an open window through which the subject to be painted is seen’. Likewise those trompe l’oeil artists of the next century, who conjured elaborate conceits in which the picture surface pretends to be an actual window – variously open or closed, and providing an interesting transparent screen through which a subject is viewed. Notwithstanding their representational value, however, Gore also manifested these features – the lamp post, the window frame – as literal verticals and horizontals that enhanced his painting’s factive material qualities.

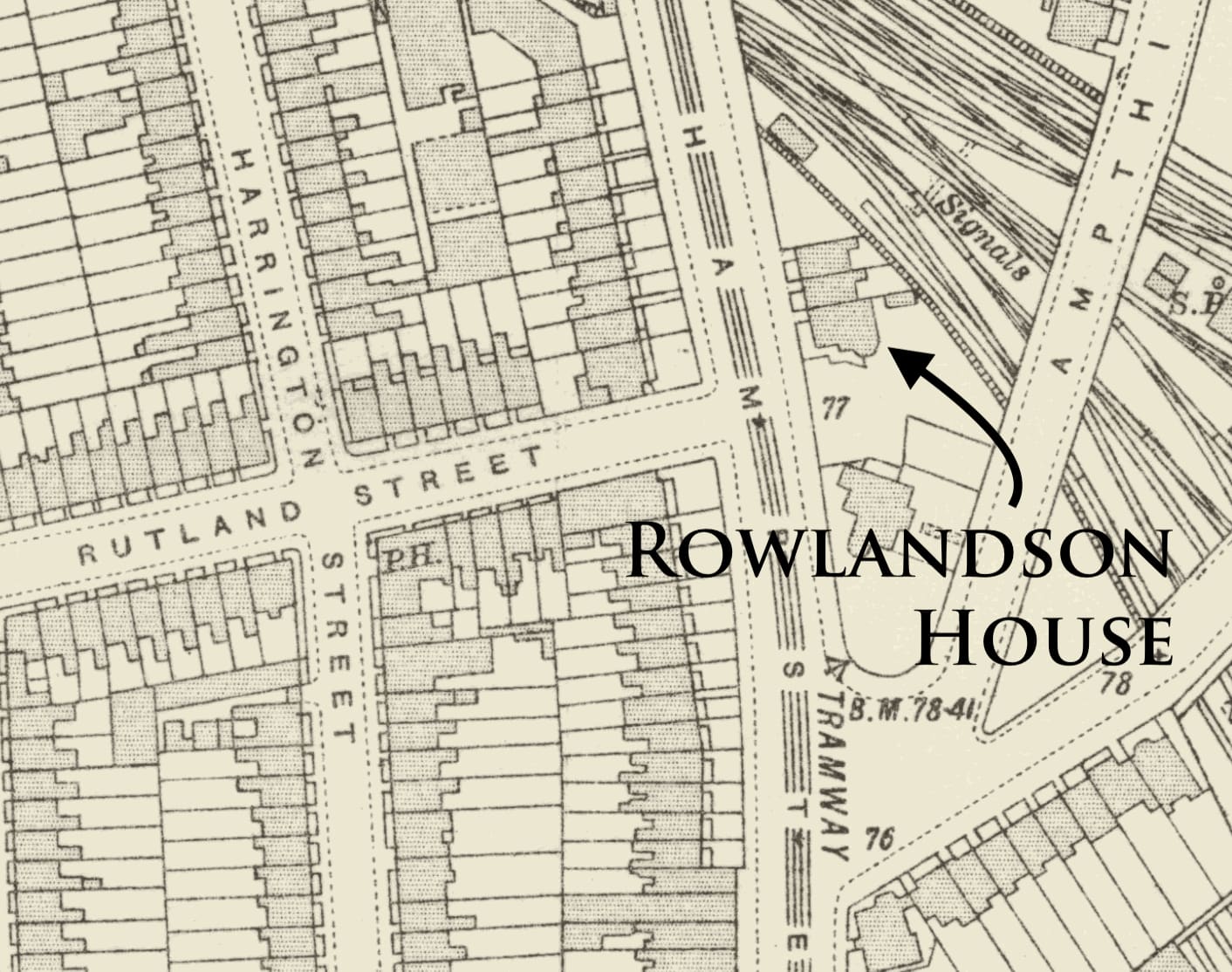

It is possible that From a Window in the Hampstead Road was exhibited as Rutland Street in Gore’s exhibition at the Carfax Gallery in 1913, held jointly with Harold Gilman who was then – like Gore – a key member of the short-lived Camden Town Group. Gore discovered his view through an upper window of Rowlandson House, No. 141 Hampstead Road, which was one of the more established of Walter Sickert’s art schools. It pictures a view across the road and down Rutland Street, which was a residential side street of Hampstead Road. (The left-hand turning half way down Rutland Street in Gore’s picture is Harrington Street, where Gilman lived for a time.) This area of London has been unrecognisable since the tired urban fabric was renewed after the Second World War, and since various street names were changed (Rutland Street became Mackworth Street sometime before 1940). But a twenty-five-inch Ordnance Survey map for 1914–16 provides a useful tool for understanding the local road layout as it was when Gore knew it.

The idea of depicting a modern city’s streets was learned from the Impressionist treatment of Paris, though London naturally gave rise to a different kind of painting. Where the likes of Monet, Pissarro and Caillebotte (as well as their erstwhile followers like the young Edvard Munch) depicted Haussman’s wide and bustling boulevards, Camden Town Group painters addressed the grubby street life and prosaic charm of North London. Gore’s painting From a Window in the Hampstead Road shows a charlady scrubbing the steps of the building opposite, illuminated in the broad noon daylight. Writing of him after his premature death in 1914, Sickert stated: ‘Gore had the digestion of an ostrich. A scene, the dreariness and hopelessness of which would strike terror into most of us, was to him matter for lyrical and exhilarated improvisation.’

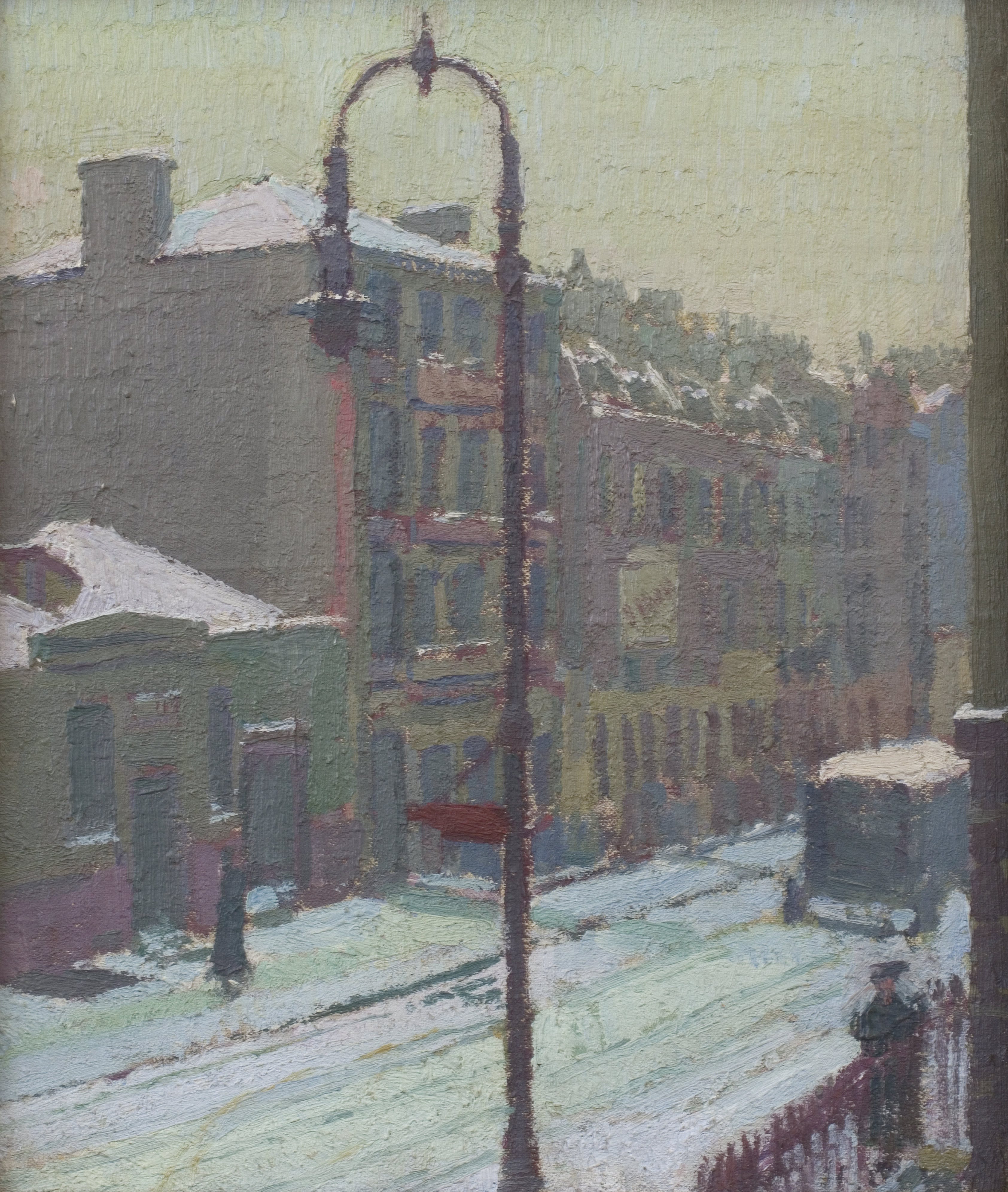

It was again Sickert who observed that ‘Monet was not the first to discover that, as the sun declines, new arrangements of light and shade arise.’ It was similarly true that the Impressionists did not have a monopoly on depicting metropolitan street scenes. Like Gore, Sickert and Gilman also painted London’s streets. A few years after Gore’s painting was made, his friend Gilman revived the street prospect with paintings such as London Street Scene in Snow, which uses the same familiar recipe of railings, receding buildings and a prominent lamp post.

In another painting by Gilman, which depicts an area along Hampstead Road, close to Rowlandson House and the site of Gore’s painting, there features a large advert for ‘the king of tobaccos’ B.D.V. – a striking billboard in bruised purple lettering against a yellow background. Including the obscured word above the logo, the billboard issues the stark imperative: ‘SMOKE B.D.V’. Such paintings as Gore’s and Gilman’s are paradigms of ‘Camden Town Group’ painting, evincing in both their subject-matter and execution the novel confrontation of an ever-changing city.

Images:

1. Spencer Gore, From a Window in the Hampstead Road, 1911, oil on canvas, 14 x 10 in

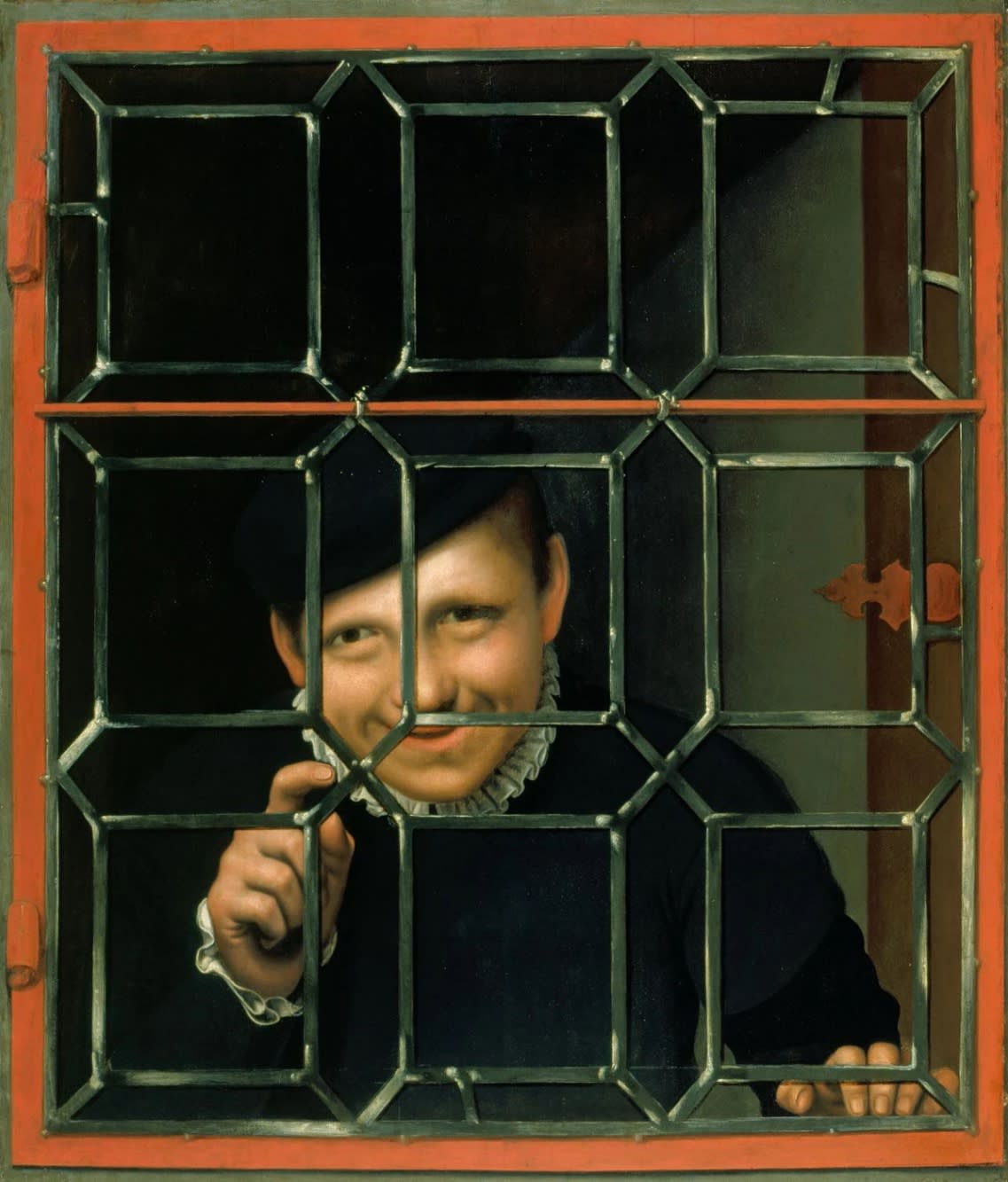

2. Flemish School, A Boy Looking through a Casement, circa 1550-1600, Royal Collection Trust

3. A postcard of Harrington Street, N.W., circa 1904, Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre

4. Ordnance Survey map for the area around Hampstead Road, 1914–1916

5. Edvard Munch, Rue Lafayette, 1891, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo

6. Harold Gilman, London Street Scene in Snow [Southampton Street, W.], 1917, Private Collection

7. Harold Gilman, Hampstead Road, circa 1910, Private Collection